Literally and Figuratively: The Use of Literalism and Moral Debate in Pro-Slavery and Abolitionist Interpretations of the Bible in the American South, 1840-1860

Historian Kathryn Long once suggested that due to “a kind of interpretive dissonance,” understanding the Revival of 1857-58 has been obscured by layers of theological writers who have attempted to illustrate the Great Awakenings as a confirmation of their own denominational understanding. Between the interpretations made by Old School Presbyterians and “New School” Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists, Long notes in her essay that the effect is awkward at best and neglectful at its worst. Hermeneutical discourse enforced two separate camps of Biblical interpretation: literalism and moral debate.

Both schools of thought were employed throughout the nineteenth century but were adopted by abolitionists as well as proslavery advocates leading up to the Civil War. Stances on slavery were not clear across denominational lines and even less clear as a result of transatlantic influences from the United Kingdom’s Ulster revival that implicitly condoned proslavery interpretations of the Bible. The Bible served as a weapon of ideological differences by both pro and anti slavery advocates through variations in their moral and literal interpretations.

New Methods of Interpretation

The emergence of new methods of Biblical interpretation resulted from the influence of empirical sciences and the accompanying anti-intellectualism that followed suit. In J. Albert Harill’s journal article regarding the use of Biblical literalism in slavery debates, he addresses the influence of empiricism on American religion by citing Charles Lyell’s 1830-33 book series, Principles of Geology, as a source that was weaponized to defend “common sense realism” interpretations of the Bible. While Lyell’s series of books contradicted divine concepts such as creationism, clergymen adopted the empirical approach to selectively defend certain ideas presented in the Bible with surface level semantics.

The best example of this principle comes from the autobiography of a fugitive slave, Samuel Ringgold Ward, who commented that in the absence of explicit condemnations against slavery in the Bible, Christians favored silence. Ward wrote that many Christians “neither hold nor treat slavery as sinful; and when pressed, declare that “some sins are not to be preached against,” thus acknowledging slavery’s sinfulness but defending its propagation through semantic technicalities.

In a seemingly oxymoronic way, common sense realism allowed individuals to interpret the Bible based on one’s own intuition and trust in his own senses which literalists then employed to take the Bible’s word at face value. This line of thought, which Harill attributes to the legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment, also bred a morally based interpretation of the Bible since meaning could be derived from the interpreter’s intuition. Empiricism, first employed to defend the presentation of the scripture, had an adverse effect as it allowed moralists to insert their own judgements into Biblical interpretations.

The New Testament and Pro-Slavery Arguments

Looking at the New Testament, the clash between literal and moral interpretations is clear. Proslavery literalists were quick to point out that Jesus Christ never explicitly condemned slavery and slaveholders in the Bible and used his silence as a work-around for proslavery debates. However, the omission of an outright condemnation was not evidence enough for outspoken abolitionist and Presbyterian minister, George Bourne. In his 90-page essay written in 1845, Bourne identified faults in literalist interpretations and pointed out that “the word “political” is not found in the Bible…any more than the word “moral,” neither is directly addressed yet literalists defended the political institution of slavery using the Bible but purposely ignored its moral implications. The omission of contemporary terms is to be expected as the Bible underwent several translations, thus Bourne saw this as a weak point of argumentation.

A simple explanation made by abolitionists is that Jesus never condemned sins which he did not witness, which explains why polygamy, sodomy, and idolatry are never directly condemned though each is “clearly a sin.” Bourne went on to say that it is impossible to separate political and moral action described in the Bible, as proslavery arguments “[attempted] to do,” however, Bourne asserted that they were “inseparable by their natures.” To Bourne, the use of only semantics was not a fair interpretation of the Bible and he urged the public to take a moral perspective when examining the relationship between religion and slavery. The politics of slavery did not divorce its morality from Biblical scrutiny.

“Are not all men born free and equal?

— Samuel Ringgold Ward, 1855

How is it, then, that I must wear these chains?”

Proslavery apologists continued to justify slavery using the New Testament’s reference to “masters” and slaves in conjunction with the relationship between Philemon and Onesmius, thought to be a master and his slave. With a letter to Philemon written by the Apostle Paul, literalist interpretations worked to align American legal conventions regarding fugitive slaves with Paul’s endorsement of allowing escaped slaves to be returned home. The word “doulos” was used to describe Onesmius’ status with his assumed master, Philemon, and was interpreted as a synonym to the modern term for “slave.” Bourne asserted that this semantic argument was inefficient because the etymology of doulos was more akin to a voluntary servant.

The Bible and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

Deuteronomy 23:15 stated, “Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which has escaped from his master unto thee.” However, in Paul’s letter to Philemon, he encourages Philemon to accept the escaped Onesmius back into his home as he would a brother. This message was interpreted by proslavery advocates as a justification for the Fugitive Slave Act, despite Paul’s explicit statement to treat Onesmius with kindness as opposed to punishment, something that Romans in the Old Testament would have inflicted upon their escaped slaves. The New Testament would have effectively neutralized the Old Testament scripture that allowed for the punishment of runaway slaves, yet this doctrine was used in service of slaveholders and slave catchers. Despite literal interpretations that implicitly undermined the Old Testament institution of punishment against slaves, proslavery advocates continued to use literal Biblicism to uphold American slavery.

As a response to proslavery literalist interpretations, abolitionists turned to arguments of morality that illustrated the Bible as a guiding compass for morality rather than a book of codes that should be followed to the letter. As a result, moralists searched for the implicit themes encoded in the scripture which produced Jesus’ “Golden Rule” which is found in Matthew 7:12 and Luke 6:31 that reads, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” This message rang loud and true among abolitionists, including former slaves who saw the hypocrisy in the literalist approach and the continued treatment of slaves as property.

In Samuel Ringgold Ward’s autobiography, Ward pleaded with slaveholders using a moral argument coupled with a message of nationalism when he wrote, “I beseech you, gentlemen, as you love your own liberty, break these chains of mine … Are not all men born free and equal? How is it, then, that I must wear these chains?” Ward’s “emotional” perspective on the issue of slavery exemplified precisely what Old School Reform groups hoped to avoid by promoting individual piety rather than progressive moral interpretations of the Bible. Ward noted that the defense of slavery using the Bible infected “all denominations” of Christianity, but literalist interpretations were pushed most heavily by Old School groups present in the North and the South.

The Impact of Religious Revivals on Slavery Debates

Kathryn Long’s essay on the 1857-58 Revival supports the argument that Biblical interpretation aligned with political ideals rather than along religious sects in the debate of slavery on a domestic and transatlantic scale. The 1857-58 Revival, being the most contemporary in relation to slavery and the Civil War, caused religious tensions and schisms that largely ignored the issue of slavery, thus igniting outspoken abolitionists and proslavery pundits even further. Long notes that the debate around slavery does not fit into the revivalist framework as many Revivalists were not concerned with progressive activism as much as they were with the general decorum of piety and individual relationships with God. The willing suppression of the slavery debate by the various sects of Christianity was done in an effort to keep the nation united in the face of such contentious ideologies but ultimately produced the opposite effect.

During one of his visits to New York, Irish Presbyterian minister Isaac Nelson commented that some revivalists wanted “to combat abolitionism and preserve church union;” but, he “believed that chattel slavery was a sin so obvious” that he was ultimately disappointed in American Revival efforts. His critique of New York is especially notable as it was the epicenter of the Revival yet had an outspoken number of proslavery advocates who did not want to jeopardize their economic relationship with the South by denouncing slavery.

Moreover, Nelson was disappointed in other British and Irish ministers who visited America and stayed silent on the issue of slavery. Rather than address the issues of slavery, British, Scottish, and Irish ministers who made frequent transatlantic journeys carried the Revival back to the United Kingdom which can be seen in the 1859 Ulster Revival that glorified an individual’s ability to connect with God and establish communal unity, which by extension glorified individual rights and nationalism. Nelson saw the outbreak of the Civil War as the ultimate proof that American revivalism failed because it actively ignored both literalist, moralist, and political cries for abolition.

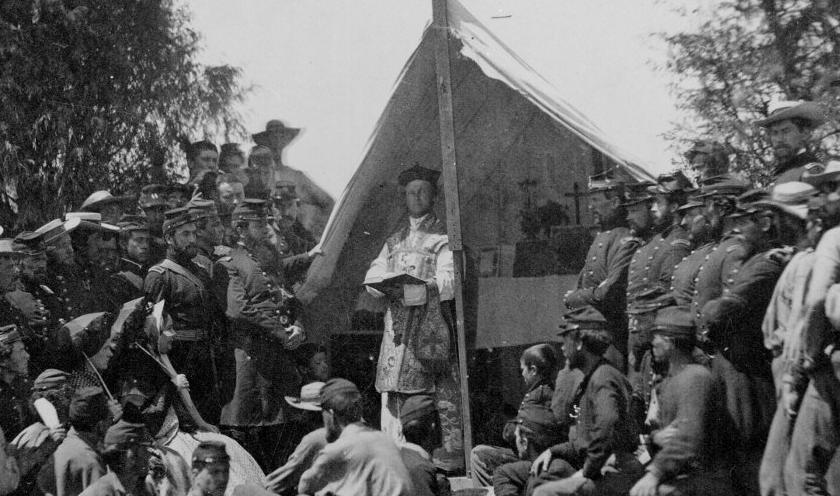

Attitudes During The Civil War

In the midst of the Civil War, members of the 1862 Confederate Bible Convention continued to willingly ignore Biblical arguments of slavery and focused instead on Northern hostility. Augusta, Georgia, where the convention was held, had a slave population that was roughly 10% to 25% of the county’s entire population. The preface of the convention stated that the members of the society “have resisted every attempt to implicate its management in the difficulties incident to the controversy” of slavery and “[urged] patriotism, benevolence, [and] personal purity” in the face of the “[North’s] arrayed hostility against the Confederate States.” The values of nationalism and an emphasis on individual liberties quashed the clarion call made by abolitionists. To further comment on morality, the Confederate Bible Convention responded with, “in morals, we have no rights of legislation,” not even in the Bible.

The Bible was weaponized by both proslavery zealots and moralist abolitionists who interpreted the scripture in a way that served their personal agendas. The “interpretive dissonance” Long coined in reference 1857-58 Revival fit the schema of the slave debate that had begun decades prior and continued for the years to follow. Even within the Revival, slavery was a hot-button issue that many, including foreign ministers, chose to ignore which ultimately escalated the tensions between the North and South until the break of the Civil War. Due to the moral rift caused by different forms of Biblical exegesis, both sides considered the other irredeemable and were never able to find common ground on the debate of slavery.

Written by N. Keegan, Communication Studies and History Major, LMU 2022.

For Further Reading

Primary Sources

Bourne, George. A Condensed Anti-slavery Bible Argument, by a citizan of Virginia. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/bourne/menu.html.

Pierce, George. Bible Convention of the Confederate States of America, 1862: Augusta, GA. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. https://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/biblconv/biblconv.html.

Steinwehr, Adolph von. Map Showing the Distribution of Slaves in the Southern States, [n. p., n. d.]. Printed Map. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/96685918

Ward, Samuel Ringgold. Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-slavery Labours in the United States, Canada, & England. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wards/ward.html

Secondary Sources

Harrill, James Albert. “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy: A Case History in the Hermeneutical Tension between Biblical Criticism and Christian Moral Debate.” In Slaves in the New Testament: Literary, Social, and Moral Dimensions, 149-186. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006.

Long, Kathryn.. “The Power of Interpretation: The Revival of 1857-58 and the Historiography of Revivalism in America.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation. 4, no. 1 (1994): 77-105.

Ritchie, D. “Transatlantic Delusions and Pro-Slavery Religion: Isaac Nelson’s Evangelical Abolitionist Critique of Revivalism in America and Ulster.” Journal of American Studies 48, no. 3 (2014): 757-776.